The Master and Student

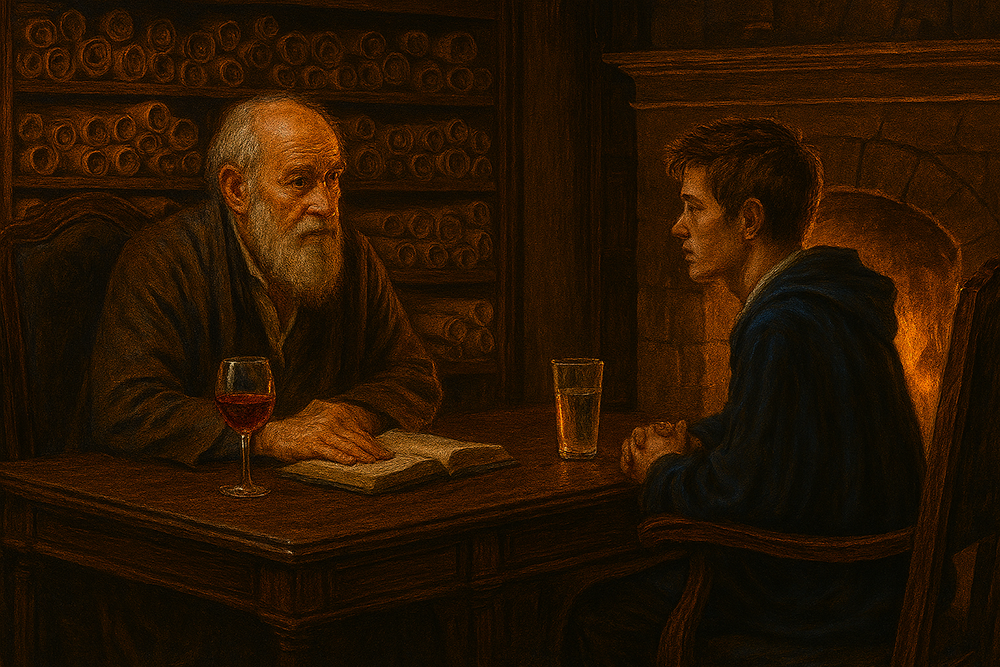

The wizened old man invited the fresh-faced youth into his study.

“Please, sit—and take a glass of port wine. I had it imported from Valoria. Sadly, this is my last bottle. Happily, I have some brandy from Sarim.”

The lanky boy sank into a comfortable leather chair.

The wizard tended the fire with a long metal poker as he began to speak. “What you must understand is that there is balance in all things.” He set another log on the fire. It rolled off and landed at his feet. “Sometimes it can be hard to achieve.” He chuckled.

The boy sat still, unsure how to react.

“I am Grand Old Enchanter of Lorien.” He laughed. “I was not so old when I was given the title, mind you.”

The boy remained silent and simply nodded. The merest twitch at the corners of his mouth suggested he understood the joke.

The wizard sank into his chair and rested his elbows on his deep chestnut desk. “Every wizard is cut from different cloth. But the rules are the same.”

The youth nodded again.

“I will try not to lecture you, and I’ll keep this first lesson brief.” He poured a measure of deep red port into a glass and offered it; the lad waved it away. “Each to his own. If you prefer something else, ask, and I’ll see what I can do.”

“Water, please,” the boy replied.

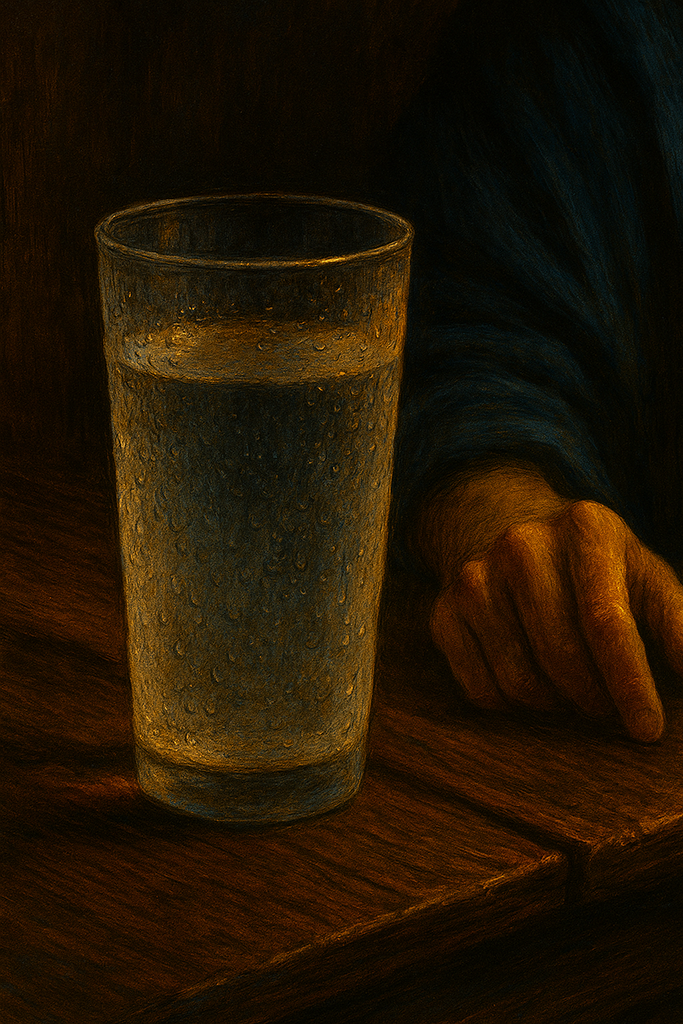

The Grand Old Enchanter placed an empty glass between them. “Watch.”

He closed his eyes and began to make his request. As he spoke the ancient words, he fixed his mind on what he needed and why. His hands moved in slow circles above the glass.

The rim misted. Beads gathered and slid down the inside. After a few minutes, the glass stood half full.

“Now, Lleuyn, do you understand what has happened?” the wizard asked, looking up at the boy’s wide eyes.

“No, Grand Old Enchanter Briac. Can you teach me?”

“Yes. We can teach you this and more. But first you must understand one thing, and one thing alone.”

Now the boy leaned forward.

“Balance: what you ask, what is given, and what is returned.”

Lleuyn nodded.

“To fill the glass, I followed the steps. This is true for something simple and small—or grand and massive.”

“What are the steps?”

“Clear your mind. Recite the words that open the gateway to the Anima Mata, the Universe. Ask, through the words, for what you seek. And at all times, consider the opposite.”

“What you sense of the Everflow is yours alone—no two people perceive it the same.”

Grand Old Enchanter Briac locked eyes with young Lleuyn. “Words open; intent guides; Everflow answers; balance repays,” he said, each pair, an instruction.

Lleuyn recoiled slightly, then recovered and leaned forward, “Please, go on…”

“You will use the Everflow to do work. Everflow comes from Anima Mata. You come from Anima Mata, as does everything. The Everflow is in everything, but only a few can shape it.”

“I was chosen?”

“Yes. No.” Briac shrugged, “No one knows why some can and others cannot. Some are strong, able to move vast currents. Others, only a trickle. Some hold fine control; others have none at first. All can learn some control—only the path differs.”

“I understand. Will I be tested, to see what I have…?”

“No. We’ll not test or judge you at the threshold. Your path is yours, whichever trail the Anima Mata sets before you.”

“You said balance, and that I should consider the opposite. What does that mean?”

“To make the water, I asked that heat be removed. The moisture in the air condensed. But consider this: where did the heat go?”

The boy’s mouth fell open as possibilities chased one another.

Briac chuckled. “Do not worry. There are many answers. There is no single correct way—only the way that suits your working. In this case,”—he nudged the glass toward the boy—“I asked the fire to take the heat.”

He sipped his port. “Another day, you might send it into stone, or into your own fatigue—though that would be unwise.”

“To lighten something here,” he added, “weight may need to settle there. To push in one place, something yields in another.”

“Be mindful, or be mindless—you decide. Do you control it, or let chance and the Anima Mata enforce the balance?”

The boy sipped his cold water.

“When I say I asked,” Briac continued, “know that there are many ways to ask—and many ways to be answered. Here, I used the Everflow alone. Sometimes the spirits may help. Sometimes you’ll know it; sometimes you won’t.”

“Can I always ask?”

“You may always ask. The answer may not be the same. You can try to demand, but that is not a path we teach or condone.” Briac’s eyes smiled.

“Is nothing definite? Is all chance and possibility?”

“The Everflow has no intent to forgive; it simply corrects. So, yes and no,” Briac said, his face wrinkling with genuine mirth. “You’ll tire of that answer. But hear this: you cannot make something from nothing. You move, change, or bind. Some things simply are. Others are equally not.”

“So—where did the heat go?” Lleuyn persisted.

“Good. You kept the thread.” The wizard paused. “As I said, I gave it to the fire. Persistence is a good quality; keep it.”

The lad smiled. “That makes sense.”

“A sharp mind—useful,” Briac said, laughing softly. “If only to make sense of the nonsense people insist on calling magic.”

“You say there is balance, and that we ask for action. What does that mean for cost?” Lleuyn asked, suddenly serious.

“It means just that. The words we recite are requests, carried by intent. Every action has a counter. For the cold water, there was heat. To move an object, something else may slow. Who knows? Some parts we guide or suggest; some we leave to the Anima Mata to settle.”

“Isn’t that dangerous—to not know the consequences?”

“That,” Briac said, “is the best question I’ve heard from a new student in a long time. This is why we are careful.”

Lleuyn’s eyes glittered in the firelight.

“A true master considers and prepares for consequence, and ensures the balance is kept. A poor wizard does not. A poor wizard is a dangerous beast. Through study of history, of method, and of self, you may become powerful without becoming dangerous.”

The boy touched a finger to his lips. “And what happens to a dangerous, or poor, wizard?”

“It depends. If they harm others, they will be fed Spellbane root and lose their connection to the Everflow. If they are merely careless, they may harm themselves—which is punishment enough.”

“And if I prove a poor student? What then?”

Briac’s expression grew grave. “Then we must judge. We may ask the Anima Mata to take your connection. Or you may choose solitude to find your true self and learn control. If there is no other option, you will live among us—but segregated, Spellbane in your diet—so none come to harm.”

“I see. Thank you, Grand Old Enchanter Briac. May I leave? I have much to consider.”

“Yes, Lleuyn. Think on what I have said—or not said. Come back with questions. I cannot promise answers.”

Lleuyn finished his water and stood.

He reached the door and turned. “The Anima Mata is everything. Everflow comes from the Anima Mata. Is the Anima Mata intelligent?”

Briac considered his answers carefully.

“Yes. No.” He shrugged. “For us, it simply is. Perhaps it is too great for us to comprehend. Maybe it is a child?”

“I see, Grand Old Enchanter.”

Briac waved his hand. The door closed quietly behind the young man.

“A lot of potential,” he said to the empty room. “A good number of questions. I fear any man—or wizard—who does not ask questions.”